Turkish people

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Row 1: Leyla Gencer • Aydın Sayılı • Halide Edip Adıvar • Mimar Kemaleddin Bey • Feriha Tevfik • İbrahim Şinasi • Fatma Aliye Topuz Row 2: Namık Kemal • Cahide Sonku • Mustafa Kemal Atatürk • Sabiha Gökçen • Besim Ömer Akalın • Nigâr Hanım • Tevfik Fikret |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (disputed) 58 - 70 million

(see also Turkish population & Turkish diaspora) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Predominantly Sunni Islam. Shia muslim, eastern orthodox and atheist minorities. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Footnotes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a Estimates suggest there are now over 4 million people of Turkish descent living in Germany.[50] However, close to 500,000 are ethnic Kurds from Turkey..[51]

b Some sources believe the figure to be as high as 1.5 million.[52] |

The Turkish people (Turkish: Türkler), also known as the "Turks", are an ethnic group of the Turkic peoples speaking the Turkish language as the mother tongue and primarily living in Turkey and in the former lands of the Ottoman Turkish Empire (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece, Iraq, Kosovo, Macedonia, Romania and Syria). In addition, during the last 50 years, a large Turkish community has been established in Europe (particularly in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium and Liechtenstein), the Middle East, North America, and Australia.

Contents |

Etymology

The name Turk (Old Turkic: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Türük[63][64] or

Türük[63][64] or ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Kök Türük[63][64] or

Kök Türük[63][64] or ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Türük,[65] Chinese: 突厥, Pinyin: Tūjué, Wade-Giles: T'u-chüeh, Middle Chinese (Guangyun): dʰuət-kĭwɐt) was first applied to a clan of tribal chieftains (known as Ashina) who overthrew the ruling Rouran Khaganate, and founded the nomadic Göktürk Khaganate ("Celestial Turks")[66] These nomads roamed in the Altai Mountains (and thus are known as Altaic peoples) in northern Mongolia and on the steppes of Central Asia.[67] Türks name refers to two distinct entities, both the confederation of medieval Inner Asia, Kok Turks and the Turks of modern Turkey.[68]

Türük,[65] Chinese: 突厥, Pinyin: Tūjué, Wade-Giles: T'u-chüeh, Middle Chinese (Guangyun): dʰuət-kĭwɐt) was first applied to a clan of tribal chieftains (known as Ashina) who overthrew the ruling Rouran Khaganate, and founded the nomadic Göktürk Khaganate ("Celestial Turks")[66] These nomads roamed in the Altai Mountains (and thus are known as Altaic peoples) in northern Mongolia and on the steppes of Central Asia.[67] Türks name refers to two distinct entities, both the confederation of medieval Inner Asia, Kok Turks and the Turks of modern Turkey.[68]

The name Türk spread as a political designation during the period of Göktürk imperial hegemony to their subject Turkic and non-Turkic peoples. Subsequently, it was adopted as a generic ethnonym designating most if not all of the Turkish-speaking tribes in Central Asia by the Muslim peoples with whom they came into contact. The imperial era also provided a legacy of political and social organisation (with deep roots in pre-Türk Inner Asia) that in its Türk form became the common inheritance of the Turkic groupings of Central Asia.[69]

History

Origins

Turkic people originated in the vicinity of Altai in Central Asia.[70] The first nomadic empire founded in present day Mongolia was Xiongnu. Some academic scholars argue that ruling class of Xiongnu Empire was proto-Turkic.[71][72] Xiongnu is sometimes considered related to Huns who were Turkic-speaking peoples according to Richard Frucht.[73] The Kök Türk (or simply Turks) formed the first khanate which uses the word Turk in state name. Kök Türk khan Bilge Khan, his brother Kül Tegin and his prime minister Tonyukuk, immortalized their accomplishments with inscriptions in the Old Turkic script,[74] the oldest known Turkish writings .[75]

The migration of Turks to the country now called Turkey occurred during the main Turkic migration. In the migration period, Turkic language, confined in the sixth century AD to a small region exploded over a vast region including most parts of Central Asia, Turkestan, north of Black Sea, Anatolia, Iran between the sixth and thirteenth centuries.[76] Oghuz Turks who were called Turkomen after becoming Muslim were the main source for Turkic migration to Anatolia. The process was accelerated after the Battle of Manzikert victory of Seljuks against the Romans; Anatolia would be called Turchia in the West as early as the 12th century.[77] The Mongols invaded Transoxiana, Iran, Azerbaijan and Anatolia; this caused Turkomens to move further to Western Anatolia.[78] In the case of the migrations, the Turkic peoples assimilated some of the Indo-European peoples encountered; Tocharian as well as the numerous Iranian speakers across the Asiatic steppe were switched to the Turkic language, and ultimatately the Greek, the majority language of Anatolia, declined in favour Turkish.[79] The Turkish ethnicity emerged gradually during the process of settlement of the Turcomens in Turkey; Turkomens were designated Turks later.

Seljuk era

The Seljuks (Turkish Selçuklular; Persian: سلجوقيان Ṣaljūqīyān; Arabic سلجوق Saljūq, or السلاجقة al-Salājiqa) were a Turkish tribe from Central Asia.[80] In 1037, they entered Persia and established their first powerful state, called by historians the Empire of the Great Seljuks. They captured Baghdad in 1055 and a relatively small contingent of warriors (around 5,000 by some estimates) moved into eastern Anatolia. In 1071, the Seljuks engaged the armies of the Byzantine Empire at Manzikert (Malazgirt), north of Lake Van. The Byzantines experienced minor casualties despite the fact that Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes was captured. With no potent Byzantine force to stop them, the Seljuks took control of most of Eastern and Central Anatolia.[81] They established their capital at Konya and ruled what would be known as the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. The success of the Seljuk Turks stimulated a response from Latin Europe in the form of the First Crusade.[82] A counteroffensive launched in 1097 by the Byzantines with the aid of the Crusaders dealt the Seljuks a decisive defeat. Konya fell to the Crusaders, and after a few years of campaigning, Byzantine rule was restored in the western third of Anatolia. Although a Turkish revival in the 1140s nullified much of the Christian gains, greater damage was done to Byzantine security by dynastic strife in Constantinople in which the largely French contingents of the Fourth Crusade and their Venetian allies intervened. In 1204, these Crusaders conquered Constantinople and installed Count Baldwin of Flanders in the Byzantine capital as emperor of the so-called Latin Empire of Constantinople, dismembering the old realm into tributary states where West European feudal institutions were transplanted intact. Independent Greek kingdoms were established at Nicaea (present-day Iznik), Trebizond (present-day Trabzon), and Epirus from remnant Byzantine provinces. Turks allied with Greeks in Anatolia against the Latins, and Greeks with Turks against the Mongols. In 1261, Michael Palaeologus of Nicaea drove the Latins from Constantinople and restored the Byzantine Empire. Seljuk Rum survived in the late 13th century as a vassal state of the Mongol Empire, who had already subjugated the Abbasid Caliphate at Baghdad. Mongol influence in the region had disappeared by the 1330s, leaving behind gazi emirates competing for supremacy. From the chaotic conditions that prevailed throughout the Middle East, however, a new power was to emerge in Anatolia, the Ottoman Turks.[83]

Beyliks era

Anatolian Beyliks (Turkish: Anadolu Beylikleri, Ottoman Turkish: Tevâif-i mülûk) were small Turkish principalities governed by Beys, which were founded across Anatolia at the end of the 11th century. Political unity in Anatolia was disrupted from the time of the collapse of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum at the beginning of the 14th century, when until the beginning of the 16th century each of the regions in the country fell under the domination of beyliks (principalities). Eventually, the Ottoman principality, which subjugated the other principalities and restored political unity in the larger part of Anatolia, was established in the Eskişehir, Bilecik and Bursa areas.[84] On the other hand, the area in central Anatolia east of the Ankara-Aksaray line as far as the area of Erzurum remained under the administration of the Ilhani General Governor until 1336. The infighting in Ilhan gave the principalities in Anatolia their complete independence. In addition to this, new Turkish principalities were formed in the localities previously under Ilhan occupation.

During the 14th century, the Turkomans, who made up the western Turks, started to re-establish their previous political sovereignty in the Islamic world. Rapid developments in the Turkish language and culture took place during the time of the Anatolian principalities. In this period, the Turkish language began to be used in the sciences and in literature, and became the official language of the principalities. New medreses were established and progress was made in the medical sciences during this period.

Ottoman era

The Ottoman Empire (Old Ottoman Turkish: دولت عالیه عثمانیه Devlet-i Âliye-yi Osmâniyye, Late Ottoman and Modern Turkish: Osmanlı Devleti or Osmanlı İmparatorluğu), was a Turkish state. The state was known as the Turkish Empire or Turkey by its contemporaries. (See the other names of the Ottoman State.) Starting as a small tribe whose territory bordered on the Byzantine frontier, the Ottoman Turks built an empire that at the height of its power (16th–17th century), spanned three continents, controlling much of Southeastern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa.

As the power of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum weakened in the late 13th century, warrior chieftains claimed the lands of Northwestern Anatolia, along the Byzantine Empire's borders. Ertuğrul gazi ruled the lands around Söğüt, a town between Bursa and Eskisehir. Upon his death in 1281, his son, Osman, from whom the Ottoman dynasty and the Empire took its name, expanded the territory to 16,000 square kilometers. Osman I, who was given the nickname "Kara" (Turkish for black) for his courage,[85] extended the frontiers of Ottoman settlement towards the edge of the Byzantine Empire. He shaped the early political development of the state and moved the Ottoman capital to Bursa.

By 1452 the Ottomans controlled almost all of the former Byzantine lands except Constantinople. On May 29, 1453, Mehmed the Conqueror captured Constantinople after a 53-day siege and proclaimed that the city was now the new capital of his Ottoman Empire.[86] Sultan Mehmed's first duty was to rejuvenate the city economically, creating the Grand Bazaar and inviting the fleeing Orthodox and Catholic inhabitants to return. Captured prisoners were freed to settle in the city whilst provincial governors in Rumelia and Anatolia were ordered to send four thousand families to settle in the city, whether Muslim, Christian or Jew, to form a unique cosmopolitan society.

During the growth of the Ottoman Empire (also known as the Pax Ottomana), Selim I extended Ottoman sovereignty southward, conquering Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. He also gained recognition as guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina; he accepted pious the title of The Servant of The Two Holy Shrines.[87][88]

Suleiman I was known in the West as "Suleiman the Magnificent"[89] and in the East, as "the Lawgiver" (in Turkish Kanuni; Arabic: القانونى, al‐Qānūnī), for his complete restructuring of the Ottoman legal system. The reign of Suleiman the Magnificent is known as the "Ottoman golden age". The brilliance of the Sultan's court and the might of his armies outshone those of England's Henry VIII, France's François I, and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. When Suleiman died in 1566, the Ottoman Empire was a world power. Most of the great cities of Islam (Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Damascus, Cairo, Tunis, and Baghdad) were under the sultan's crescent flag. After Suleiman, however, the empire's power gradually diminished due to poor leadership; many successive Sultans largely depended upon their Grand Viziers to run the state affairs.

The Ottoman sultanate lasted for 624 years, but its last three centuries were marked by stagnation and eventual decline. By the 19th century, the Ottomans had fallen well behind the rest of Europe in science, technology, and industry. Reformist Sultans such as Selim III and Mahmud II succeeded in pushing Ottoman bureaucracy, society and culture ahead, but were unable to cure all of the empire's ills. Despite its collapse, the Ottoman empire has left an indelible mark on Turkish culture and architecture. Ottoman culture has given the Turkish people a splendid legacy of art, architecture and domestic refinement, as a visit to Istanbul's Topkapi Palace readily shows.

The Republic of Turkey

.jpg)

The Republic of Turkey was born from the disastrous World War I defeat of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman war hero, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (who was later given the surname Atatürk by the Turkish Parliament with the Surname Law of 1934), sailed from Istanbul to Samsun in May 1919 to start the Turkish liberation movement; he organized the remnants of the Ottoman army in Anatolia into an effective fighting force, and rallied the people to the nationalist cause. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, a military commander who had distinguished himself during the Battle of Gallipoli, the Turkish War of Independence was waged with the aim of revoking the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres.[90] By 1923 the nationalist government had driven out the invading armies; replaced the Treaty of Sèvres with the Treaty of Lausanne and abolished the Ottoman State; promulgated a republican constitution; and established Turkey's new capital in Ankara.[91]

During a meeting in the early days of the new republic, Atatürk proclaimed:

To the women: Win for us the battle of education and you will do yet more for your country than we have been able to do. It is to you that I appeal.

To the men: If henceforward the women do not share in the social life of the nation, we shall never attain to our full development. We shall remain irremediably backward, incapable of treating on equal terms with the civilizations of the West.[92]—Mustafa Kemal

The Kemalist revolution aimed to create a Turkish nation state (Turkish: ulus devlet) on the territory of the former Ottoman Empire that had remained within the boundaries of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. The meaning of Turkishness (Turkish: Türklük) implies a "citizenship" (of the Republic of Turkey) and "cultural identity" (speaking the Turkish language and growing up with the mainstream Turkish culture) rather than an ethno-genetical background. The Turkish-speaking Muslim citizens of the Ottoman Empire had been called "Turks" for centuries by the Europeans, and the Ottoman Empire was alternatively called "Turkey" or the "Turkish Empire" by its contemporaries. However, the Devşirme system and intermarriages with people in the former Ottoman territories of Southeastern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa ensured a largely heterogeneous gene pool that makes up the fabric of the present-day Turkish nation. The Turks of today, in short, are the descendants of the Turkic-speaking Muslims in the former Ottoman Empire.

| “ | Ne Mutlu Türküm Diyene (How happy is he/she who calls himself/herself a Turk). | ” |

| “ | Ne Mutlu Türküm Diyebiline (How happy is he/she who can call himself/herself a Turk). | ” |

|

—Mahmut Esat Bozkurt |

||

Genetics

It is difficult to understand the complex cultural and demographic dynamics of the Turkic speaking groups that have shaped the Anatolian landscape for the last millennium.[93] During the Bronze Age the population of Anatolia expanded, reaching an estimated level of 12 million during the late Byzantine Empire period. Such a large pre-existing Anatolian population would have reduced the impact by the subsequent arrival of Turkic speaking groups from Seljuk Persia, whose ethno-linguistic roots could be traced back to the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea basin in Central Asia.[94][95] The Seljuk Turks were the main Turkic people who moved into Anatolia, starting from the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.[96][97] Around 1,000,000 Turkic migrants settled in Anatolia during the 12th and 13th centuries.[98]

The question of to what extent a gene flow from Central Asia, via Persia, to Anatolia has contributed to the current gene pool of the Turkish people, and the role of the 11th century invasion by Seljuk Turks, has been the subject of several studies. It is concluded that aboriginal Anatolian groups may have given rise to the present-day Turkish population. DNA analysis research studies suggest that the Anatolians do not significantly differ from other Mediterraneans, indicating that while the Seljuk Turks carried out a permanent territorial conquest with strong cultural, linguistic and religious significance, it is barely genetically detectable.[99]

Another significant flow into the present-day Turkish gene pool occurred during the Ottoman period, when large groups of non-Turks were culturally Turkicized through the Devshirme (Devşirme) system; including many of the leading Ottoman Grand Viziers such as Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and members of the Köprülü family. The famous Janissary (Yeniçeri) corps were entirely formed of non-Muslim children recruited at a very young age and raised with Turkish culture. Many Ottoman sultans (as well as other members of the Ottoman society) preferred to marry women from the European provinces of the empire, such as the famous sultanas Hürrem, Kösem, Nurbanu, Safiye and numerous others; and to a lesser extent with women from the Ottoman provinces in the Near East and North Africa. The naval battles between the Ottoman Empire and other European powers around the Mediterranean Sea also played an important role in large population exchanges (see, for instance, Uluç Ali Reis and Cigalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha).Greek Muslims have been absorbed into the Turkish ethnic group and many Turkish nobles have some Greek ancestry through the Ottoman practice of taking Christian wives.

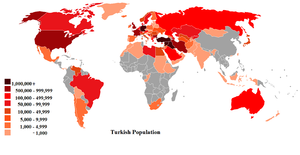

Geographic distribution

Turks primarily live in Turkey; however, when the borders of the Ottoman Empire became smaller after World War I and the new Turkish Republic was founded, many Turks chose to stay outside of Turkey's borders. Since then, some of them have migrated to Turkey but there are still significant minorities of Turks living in different countries such as in Northern Cyprus (Turkish Cypriots), Greece, Bulgaria, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Republic of Macedonia, the Dobruja region of Romania, Pakistan, the Sandžak region of Serbia, Kosovo, Syria,India, China, Countries of Central Asia and Iraq.

The three most important Turkish groups are the Anatolian Turks, the Rumelian Turks (primarily immigrants from former Ottoman territories in the Balkans and their descendants), and the Central Asian Turks (Turkic-speaking immigrants from the Caucasus region, southern Russia, and Central Asia and their descendants).

Turks in Turkey

People who identify themselves as ethnic Turks comprise 70-75% (2008),[100] 76.03% (2006),[1][2] 80-88% (1995) of Turkey's population.[101] Regions of Turkey with the largest populations are İstanbul (+12 million), Ankara (+4.4 million), İzmir (+3.7 million), Bursa (+2.4 million), Adana (+2.0 million) and Konya (+1.9 million).[102]

The biggest city and the pre-Republican capital İstanbul is the financial, economic and cultural heart of the country. Other important cities include İzmir, Bursa, Adana, Trabzon, Malatya, Gaziantep, Erzurum, Kayseri, Kocaeli, Konya, Mersin, Eskişehir, Diyarbakır, Kahramanmaraş, Antalya and Samsun. An estimated 70.5% of the Turkish population live in urban centers.[103] In all, 18 provinces have populations that exceed 1 million inhabitants, and 21 provinces have populations between 1 million and 500,000 inhabitants. Only two provinces have populations less than 100,000.

Turks in Europe

As a legacy of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, there are significant Turkish minorities in Europe such as the Turks in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Kosovo and the Republic of Macedonia.

The post-World War II migration of Turks to Europe began with ‘guest workers’ who arrived under the terms of a Labour Export Agreement with Germany in October 1961, followed by a similar agreement with the Netherlands, Belgium and Austria in 1964; France in 1965 and Sweden in 1967. As one Turkish observer noted, ‘it has now been over 40 years and a Turk who went to Europe at the age of 25 has nearly reached the age of 70. His children have reached the age of 45 and their children have reached the age of 20’.[104]

Despite the United Kingdom not being part of the Labour Export Agreement, it is still a major hub for Turkish emigrants, and with a population of half a million Turks[105] (an estimated 100,000 Turkish nationals and 130,000 nationals of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus currently live in the UK. These figures, however, do not include the much larger numbers of Turkish speakers who have been born or have obtained British nationality),[106] it is home to Europe's third largest Turkish community. High immigration has resulted in the Turkish language being the seventh most commonly spoken language in the United Kingdom.[107]

Due to the high rate of Turks in Europe, the Turkish language is also now home to one of the largest group of pupils after German-speakers, and the largest non-European language spoken in the European Union. Turkish in Germany is often used not only by members of its own community but also by people with a non-Turkish background. Especially in urban areas, it functions as a peer group vernacular for children and adolescents.[108]

Turks in the Americas

Anglo-America

The US Census reported in 2006 that approximately 170,000 Americans identify as having at least partial Turkish ancestry,[109] while the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History states that there is an estimated 500,000 Turks living in the United States;[13] the largest Turkish communities are found in Paterson, New York City (i.e. Brooklyn and Staten Island), Long Island, Cleveland, Chicago, Houston, Miami, Washington D.C. (mostly in Northern Virginia), Boston (esp. the suburb of Watertown), Philadelphia, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Since the 1970s, the number of Turkish immigrants has risen to more than 4,000 per year. There is also a growing Turkish population in Canada, Turkish immigrants have settled mainly in Montreal and Toronto, although there are small Turkish communities in Calgary, Edmonton, London, Ottawa, and Vancouver. The population of Turkish Canadians in Metropolitan Toronto may be as large as 5,000.[110]

Latin America

Turkish immigrants can be found in smaller numbers in Latin America, limited to Chile (about 1,000), Brazil (estimated at 5,000) and Mexico (fewer than 2,000). They are not to be confused with heavily numerous Christian Arab immigrants called "Turcos", an inaccurate name for Lebanese and Syrian refugees, due to the nickname came from their "Turkish" nationality passports on arrival, whom fled the Ottoman Empire in the 1910s and 1920s. Both ethnic Turk and smaller "Turco" Arab communities can be found in South America, Central America and the Caribbean.

Culture

Turkish people have a very diverse culture that is a blend of various elements of the Oğuz Turkic and Anatolian, Ottoman, and Western culture and traditions which started with the Westernization of the Ottoman Empire and continues today. This mix is a result of the encounter of Turks and their culture with those of the peoples inhabitaing the areas of their migration from Central Asia to the West.[111][112] As Turkey successfully transformed from the religion-based former Ottoman Empire into a modern nation-state with a very strong separation of state and religion, an increase in the methods of artistic expression followed. During the first years of the republic, the government invested a large amount of resources into fine arts, such as museums, theatres, and architecture. Because of different historical factors playing an important role in defining the modern Turkish identity, Turkish culture is a product of efforts to be "modern" and Western, combined with the necessity felt to maintain traditional religious and historical values.[111]

Language

The Turkish language is a member of the ancient Oghuz subdivision of Turkic languages, which in turn is a branch of the proposed Altaic language family.[113][114][115] About 40% of Turkic language speakers are Turkish speakers.[116] Turkish is for the most part, mutually intelligible with other Oghuz languages like Azerbaijani Turkish, Crimean Tatar, Gagauz, Turkmen and Urum, and to a lesser extent with other Turkic languages.

With the Turkic expansion during Early Middle Ages (c. 6th–11th centuries), peoples speaking Turkic languages spread across Central Asia, covering a vast geographical region stretching from Siberia to Europe and the Mediterranean. The Seljuqs of the Oghuz Turks, in particular, brought their language, Oghuz Turkic—the direct ancestor of today's Turkish language—into Anatolia during the 11th century.[117] Also during the 11th century, an early linguist of the Turkic languages, Mahmud al-Kashgari from the Kara-Khanid Khanate, published the first comprehensive Turkic language dictionary and map of the geographical distribution of Turkic speakers in the Compendium of the Turkic Dialects (Arabic: Dīwānu'l-Luġat at-Turk).[118] In 1277 Karamanoğlu Mehmet Bey declared Turkish as the sole official language of the Karamanoğlu Beylik in Anatolia.

After the foundation of the Republic of Turkey and the script reform, the Turkish Language Association (TDK) was established in 1932 under the patronage of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, with the aim of conducting research on Turkish. One of the tasks of the newly-established association was to initiate a language reform to replace loanwords of Arabic and Persian origin with Turkish equivalents.[119] By banning the usage of imported words in the press, the association succeeded in removing several hundred foreign words from the language. While most of the words introduced to the language by the TDK were newly derived from Turkic roots, it also opted for reviving Old Turkish words which had not been used for centuries.

Istanbul Turkish is established as the official standard language of Turkey. Turkish is the official language of Turkey and is one of the official languages of Cyprus. It also has official (but not primary) status in the Prizren District of Kosovo and several municipalities of Republic of Macedonia, depending on the concentration of Turkish-speaking local population.

Architecture

Turkish architecture reached its peak during the Ottoman period. Ottoman architecture, influenced by Seljuk, Byzantine and Islamic architecture, came to develop a style all of its own.[120] Overall, Ottoman architecture has been described as a synthesis of the architectural traditions of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[121]

During the zenith of the Sultanate of Rum, Seljuk architects undertook extensive public works projects. Using the abundant Anatolian stone and clay, they built mosques, medreses, and türbes. To safeguard their profitable trade in silks, spices and to provide rest for merchants, the Seljuk’s built over 100 kervansarays along Anatolian highways, each spaced a day’s ride away from the next. These rest stops featured mosques, storage rooms, stables, coffeehouses, hamams, private rooms and dormitories. The most impressive of its kind is the Sultan Han outside Kayseri. Seljuk buildings were characterised by their elaborate stone carvings. In addition to carvings, the Seljuk’s enhanced their mosques with glazed earthenware (faience) which was used to cover walls and minarets with the best examples at Konya in the Karatay Medrese.[122]

The first Ottoman capital, Bursa, is a museum of 14th and 15th century Ottoman architecture. With the capital of Istanbul in 1453, Ottoman architects were challenged to exceed the vaults and pendentives of the Hagia Sophia's dome. Ottoman architecture reached its peak under the unprecedented benefaction of Suleiman the Magnificent. During his rule alone, over 80 major mosques and hundreds of other buildings were constructed. Divan Yolu, Istanbul’s processional avenue, boasts a collection of these structural wonders. The master architect, Mimar Sinan served Suleyman and his sons as Chief Court Architect from 1538–1588, during which time he created a unified style for all Istanbul and for much of the empire.[123]

Many Ottoman mosques stand at the centre of a ‘külliye’ (complex) designed to serve all of a community’s needs. Külliyes often included a school, markets, soup kitchens and a medical centre, all integrated architecturally into a single whole. The most impressive külliyes are those of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, and the Bayezid II Mosque and Hospital in Edirne. Most külliyes were established as charitable foundations, although economic instability has jeopardised these institutions financially, many of them still function today.

16th century Ottoman architects set a powerful precedent for future structures. Buildings such as the Blue Mosque were mere imitations of the Sinan blueprint. During the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, Ottoman architecture was influenced by European styles. The first examples of Baroque architecture appeared in the 18th century, in buildings such as the Harem section of the Topkapı Palace, the Aynalıkavak Palace and the Nuruosmaniye Mosque, the latter also having a famous Baroque fountain. Numerous buildings were built in the 19th century with an eclectic mix of various European styles such as Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical architecture, including the Dolmabahçe Palace, Beylerbeyi Palace, Dolmabahçe Mosque and the Ortaköy Mosque. Some mosques were even designed with an Ottoman adaptation of the Neo-Gothic style, such as the Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque in the Aksaray quarter, and the Yıldız Hamidiye Mosque in the Yıldız quarter of Beşiktaş, close to the Yıldız Palace and the Barbaros Boulevard. Towards the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Istanbul became one of the leading centers of the Art Nouveau movement, with architects such as Alexander Vallaury and Raimondo D'Aronco designing a number of prominent buildings in this style. In the early 20th century, Turkish architects such as Mimar Kemaleddin Bey and Mimar Vedat Bey (Vedat Tek) pioneered a "Turkish neoclassical" architectural style (Turkish: Birinci Ulusal Mimarlık Akımı), using many elements from the Turkish buildings of the past centuries. The most important examples of this style include the Büyük Postane (Grand Post Office) and Vakıf Han office buildings in Istanbul's Sirkeci quarter.

Arts and calligraphy

A transition from Islamic artistic traditions under the Ottoman Empire to a more secular, Western orientation has taken place in Turkey. Turkish painters today are striving to find their own art forms, free from Western influence. Sculpture is less developed, and public monuments are usually heroic representations of Atatürk and events from the war of independence. Literature is considered the most advanced of contemporary Turkish arts. The reign of the early Ottoman Turks in the 16th and early 17th centuries introduced the Turkish form of Islamic calligraphy. This art form reached the height of its popularity during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–66). As decorative as it was communicative, Diwani was distinguished by the complexity of the line within the letter and the close juxtaposition of the letters within the word.

Music

The roots of traditional music in Turkey span centuries to a time when the Seljuk Turks colonized Anatolia and Persia in the 11th century and contains elements of both Turkic and pre-Turkic influences. Much of its modern popular music can trace its roots to the emergence in the early 1930s drive for Westernization.[124]

Traditional music in Turkey falls into two main genres; classical art music and folk music. Turkish classical music is characterized by an Ottoman elite culture and influenced lyrically by neighbouring regions and Ottoman provinces.[125] Earlier forms are sometimes termed as saray music in Turkish, meaning royal court music, indicating the source of the genre comes from Ottoman royalty as patronage and composer.[126] Neo-classical or postmodern versions of this traditional genre are termed as art music or sanat musikisi, though often it is unofficially termed as alla turca. In addition, from the saray or royal courts came the Ottoman military band, Mehter takımı in Turkish, considered to be the oldest type of military marching band in the world. It was also the forefather of modern Western percussion bands and has been described as the father of Western military music.[127]

Turkish folk music is the music of Turkish-speaking rural communities of Anatolia, the Balkans, and Middle East. While Turkish folk music contains definitive traces of the Central Asian Turkic cultures, it has also strongly influenced and been influenced by many other indigenous cultures. Religious music in Turkey is sometimes grouped with folk music due to the tradition of the wandering minstrel or aşık (pronounced ashuk), but its influences on Sufism due to the spritiual Mevlevi sect arguably grants it special status.[128] It has been suggested the distinction between the two major genres comes during the Tanzîmat period of Ottoman era, when Turkish classical music was the music played in the Ottoman palaces and folk music was played in the villages.[129]

Musical relations between the Turks and Europe can be traced back many centuries,[130] and the first type of musical Orientalism was the Turkish Style.[131] European classical composers in the 18th century were fascinated by Turkish music, particularly the strong role given to the brass and percussion instruments in Janissary bands. Joseph Haydn wrote his Military Symphony to include Turkish instruments, as well as some of his operas. Turkish instruments were also included in Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony Number 9. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote the "Ronda alla turca" in his Sonata in A major and also used Turkish themes in his operas, such as the Chorus of Janissaries from his Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782). This Turkish influence introduced the cymbals, bass drum, and bells into the symphony orchestra, where they remain. Jazz musician Dave Brubeck wrote his "Blue Rondo á la Turk" as a tribute to Mozart and Turkish music.

Literature

The literature of the Turkish Republic emerged largely from the pre-independence National Literature movement, with its roots simultaneously in the Turkish folk tradition and in the Western notion of progress. One important change to Turkish literature was enacted in 1928, when Mustafa Kemal initiated the creation and dissemination of a modified version of the Latin alphabet to replace the Arabic alphabet based Ottoman script. Over time, this change, together with changes in Turkey's system of education, would lead to more widespread literacy in the country.[132]

Prose

Stylistically, the prose of the early years of the Republic of Turkey was essentially a continuation of the National Literature movement, with Realism and Naturalism predominating. This trend culminated in the 1932 novel Yaban ("The Wilds"), by Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu. This novel can be seen as the precursor to two trends that would soon develop: social realism, and the "village novel" (köy romanı).[133] Çalıkuşu ("The Wren") by Reşat Nuri Güntekin addresses a similar theme with the works of Karaosmanoğlu. Güntekin's narrative has a detailed and precise style, with a realistic tone.

The social realist movement is perhaps best represented by the short-story writer Sait Faik Abasıyanık (1906–1954), whose work sensitively and realistically treats the lives of cosmopolitan Istanbul's lower classes and ethnic minorities, subjects which led to some criticism in the contemporary nationalistic atmosphere.[134] The tradition of the "village novel", on the other hand, arose somewhat later. As its name suggests, the "village novel" deals, in a generally realistic manner, with life in the villages and small towns of Turkey. The major writers in this tradition are Kemal Tahir (1910–1973), Orhan Kemal (1914–1970), and Yaşar Kemal (1923– ). Yaşar Kemal, in particular, has earned fame outside of Turkey not only for his novels; many of which, such as 1955's İnce Memed ("Memed, My Hawk"), elevate local tales to the level of epic; but also for his firmly leftist political stance. In a very different tradition, but evincing a similar strong political viewpoint, was the satirical short-story writer Aziz Nesin (1915–1995) and Rıfat Ilgaz (1911–1993).

Another novelist contemporary to, but outside of, the social realist and "village novel" traditions is Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar (1901–1962). In addition to being an important essayist and poet, Tanpınar wrote a number of novels; such as Huzur ("Tranquillity", 1949) and Saatleri Ayarlama Enstitüsü ("The Time Regulation Institute", 1961); which dramatize the clash between East and West in modern Turkish culture and society. Similar problems are explored by the novelist and short-story writer Oğuz Atay (1934–1977). Unlike Tanpınar, however, Atay—in such works as his long novel Tutunamayanlar ("The Disconnected", 1971–1972) and his short story "Beyaz Mantolu Adam" ("Man in a White Coat", 1975)—wrote in a more modernist and existentialist vein. On the other hand, Onat Kutlar's İshak ("Isaac", 1959), composed of nine short stories which are written mainly from a child's point of view and are often surrealistic and mystical, represent a very early example of magic realism.

The tradition of literary modernism also informs the work of novelist Adalet Ağaoğlu (1929– ). Her trilogy of novels collectively entitled Dar Zamanlar ("Tight Times", 1973–1987), for instance, examines the changes that occurred in Turkish society between the 1930s and the 1980s in a formally and technically innovative style. Orhan Pamuk (1952– ), winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, is another such innovative novelist, though his works—such as 1990's Beyaz Kale ("The White Castle") and Kara Kitap ("The Black Book") and 1998's Benim Adım Kırmızı ("My Name is Red")—are influenced more by postmodernism than by modernism. This is true also of Latife Tekin (1957– ), whose first novel Sevgili Arsız Ölüm ("Dear Shameless Death", 1983) shows the influence not only of postmodernism, but also of magic realism.

Poetry

In the early years of the Republic of Turkey, there were a number of poetic trends. Authors such as Ahmed Hâşim and Yahyâ Kemâl Beyatlı (1884–1958) continued to write important formal verse whose language was, to a great extent, a continuation of the late Ottoman tradition. By far the majority of the poetry of the time, however, was in the tradition of the folk-inspired "syllabist" movement (Beş Hececiler), which had emerged from the National Literature movement and which tended to express patriotic themes couched in the syllabic meter associated with Turkish folk poetry.

The first radical step away from this trend was taken by Nâzım Hikmet Ran, who—during his time as a student in the Soviet Union from 1921 to 1924—was exposed to the modernist poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky and others, which inspired him to start writing verse in a less formal style. At this time, he wrote the poem "Açların Gözbebekleri" ("Pupils of the Hungry"), which introduced free verse into the Turkish language for, essentially, the first time.[135] Much of Nâzım Hikmet's poetry subsequent to this breakthrough would continue to be written in free verse, though his work exerted little influence for some time due largely to censorship of his work owing to his Communist political stance, which also led to his spending several years in prison. Over time, in such books as Simavne Kadısı Oğlu Şeyh Bedreddin Destanı ("The Epic of Shaykh Bedreddin, Son of Judge Simavne", 1936) and Memleketimden İnsan Manzaraları ("Human Landscapes from My Country", 1939), he developed a voice simultaneously proclamatory and subtle.

Another revolution in Turkish poetry came about in 1941 with the publication of a small volume of verse preceded by an essay and entitled Garip ("Strange"). The authors were Orhan Veli Kanık (1914–1950), Melih Cevdet Anday (1915–2002), and Oktay Rifat (1914–1988). Explicitly opposing themselves to everything that had gone in poetry before, they sought instead to create a popular art, "to explore the people's tastes, to determine them, and to make them reign supreme over art".[136] To this end, and inspired in part by contemporary French poets like Jacques Prévert, they employed not only a variant of the free verse introduced by Nâzım Hikmet, but also highly colloquial language, and wrote primarily about mundane daily subjects and the ordinary man on the street. The reaction was immediate and polarized: most of the academic establishment and older poets vilified them, while much of the Turkish population embraced them wholeheartedly. Though the movement itself lasted only ten years—until Orhan Veli's death in 1950, after which Melih Cevdet Anday and Oktay Rifat moved on to other styles—its effect on Turkish poetry continues to be felt today.

Just as the Garip movement was a reaction against earlier poetry, so—in the 1950s and afterwards—was there a reaction against the Garip movement. The poets of this movement, soon known as İkinci Yeni ("Second New"[137]), opposed themselves to the social aspects prevalent in the poetry of Nâzım Hikmet and the Garip poets, and instead—partly inspired by the disruption of language in such Western movements as Dada and Surrealism—sought to create a more abstract poetry through the use of jarring and unexpected language, complex images, and the association of ideas. To some extent, the movement can be seen as bearing some of the characteristics of postmodern literature. The most well-known poets writing in the "Second New" vein were Turgut Uyar (1927–1985), Edip Cansever (1928–1986), Cemal Süreya (1931–1990), Ece Ayhan (1931–2002), Sezai Karakoç (1933- ) and İlhan Berk (1918– ).

Outside of the Garip and "Second New" movements also, a number of significant poets have flourished, such as Fazıl Hüsnü Dağlarca (1914– ), who wrote poems dealing with fundamental concepts like life, death, God, time, and the cosmos; Behçet Necatigil (1916–1979), whose somewhat allegorical poems explore the significance of middle-class daily life; Can Yücel (1926–1999), who—in addition to his own highly colloquial and varied poetry—was also a translator into Turkish of a variety of world literature.

Religion

The vast majority of the present-day Turkish people are Muslim and the most popular sect is the Hanafite school of Sunni Islam. Secularism in Turkey was introduced with the Turkish Constitution of 1924, and later Atatürk's Reforms set the administrative and political requirements to create a modern, secular state aligned with the Kemalist ideology. Thirteen years after its introduction, laïcité (February 5, 1937) was explicitly stated as a property of the State in the second article of the Turkish constitution. The current Turkish constitution neither recognizes an official religion nor promotes any. This includes Islam, which at least nominally more than 99% of citizens subscribe to (according to the government).[138]

See also

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 55 milyon kişi 'etnik olarak' Türk", Milliyet, 22 March 22, 2007. (Turkish)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 KONDA Research and Consultancy, Social Structure Survey 2006

- ↑ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. "Country Profile: Turkey". http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Turkey.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ↑ The Guardian (2009-04-25). "Country Profile: Turkey". London. http://www.guardian.co.uk/country-profile/turkey. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Turkey: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995. Turks

- ↑ Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany London. "Turkey: strategically important partner". http://www.london.diplo.de/Vertretung/london/en/03/__Political__News/Westerwelle/Tuerkei__Seite.html. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ↑ Park 2005, 36.

- ↑ Kibaroğlu, Kibaroğlu & Halman 2009, 165.

- ↑ National Statistics Institute of Bulgaria. "2001 census, population by ethnic group". http://www.nsi.bg/Census_e/Ethnos.htm.

- ↑ Hunter 2002, 6.

- ↑ Todays ZAMAN. "Ankara Continues to Criticize Genocide Bill". http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/detaylar.do?load=detay&link=37334. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Federation of Turkish Associations in the UK 2008, 1.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. "Immigration and Ethnicity: Turks". http://ech.case.edu/ech-cgi/article.pl?id=TIC. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ TURKISH SOCIETY OF ROCHESTER, NEW YORK. "About Turkish Society of Rochester". http://www.tsor.org/aboutus.html. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Netherlands Info Services. "Dutch Queen Tells Turkey "First Steps Taken" On EU Membership Road". http://www.nisnews.nl/public/010307_2.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ Dutch News. "Dutch Turks swindled, AFM to investigate". http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2007/03/dutch_turks_swindled_afm_to_in.php. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ SundaysZaman. "Austria signals policy changes for better relations with Turkey". http://www.sundayszaman.com/sunday/detaylar.do?load=detay&link=186277. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ↑ TRNC PRIME MINISTRY STATE PLANNING ORGANIZATION 2006, 1.

- ↑ King Baudouin Foundation 2008, 5.

- ↑ Kaya & Kentel 2007, 27.

- ↑ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia". Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office. 2002. http://www.stat.gov.mk/pdf/kniga_13.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Knowlton 2005, 66.

- ↑ Oustinova-Stjepanovic 2008, 1.

- ↑ Fred 1996, 53.

- ↑ Karpat 2004, 12.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald. "Old foes, new friends". http://www.smh.com.au/news/World/Old-foes-new-friends/2005/04/22/1114152326767.html. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ↑ Turkish Embassy AU. "Turkish National Day" (PDF). http://www.turkishembassy.org.au/assets/docs/National_day.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ↑ Western Thrace Minority University Graduates Association 2009, 2.

- ↑ Ergener & Ergener 2002, 106.

- ↑ WorldBulletin. "Western Thrace Turks tell Erdogan of problems in Greece". http://www.worldbulletin.net/news_detail.php?id=53618. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Aydıngün et al. 2006, 13.

- ↑ The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation. "Bilateral relations between Switzerland and Turkey". http://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/home/reps/eur/vtur/biltur.html. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ Centre For Russian Studies. "2002 Nationality report". http://www2.nupi.no/cgi-win//Russland/etnisk.exe?total. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Демоскоп Weekly. "Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года.". http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_nac_02.php. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ↑ ZAMAN. "Erdoğan’s visit to Stockholm and Turkish-Swedish relations". http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/yazarDetay.do?haberno=138098. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Murat, Sedat (2000). "Immigrant Turks and their socio-economic structure in European countries". İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi. http://www.cumhuriyet.edu.tr/edergi/makale/90.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ DR Online. "Tyrkisk afstand fra Islamisk Trossamfund". http://www.dr.dk/Nyheder/Indland/2008/02/21/071316.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ↑ Phinnemore 2006, 157.

- ↑ Canada's National Statistical Agency. "Statistics Canada". http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/topics/RetrieveProductTable.cfm?ALEVEL=3&APATH=3&CATNO=&DETAIL=0&DIM=&DS=99&FL=0&FREE=0&GAL=0&GC=99&GK=NA&GRP=1&IPS=&METH=0&ORDER=1&PID=92333&PTYPE=88971&RL=0&S=1&ShowAll=No&StartRow=1&SUB=801&Temporal=2006&Theme=80&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Turkish Embassy (Ottawa Canada). "TURKISH - CANADIAN RELATIONS". http://www.turkishembassy.com/II/O/Turkish_Canadian_relations.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ↑ Thomas Goltz. "Minority Within a Minority-- For Ethnic Turks, Serbian War is Another Chapter in a 600 Year Old Story". http://www.pacificnews.org/jinn/stories/5.10/990520-turks.html. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ↑ Warrander & Knaus 2008, 32.

- ↑ IRIN Asia. "KYRGYZSTAN: Focus on Mesketian Turks". http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=28663. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ Rep. of Turkey Ministry of Labour and Social Security. "YURTDISINDAKI VATANDASLARIMIZLA ILGILI SAYISAL BILGILER". http://www.calisma.gov.tr/article.php?article_id=371. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ↑ ORSAM 2010, 13-14.

- ↑ Statistiche Demografiche ISTAT. "Resident Population by sex and citizenship (Middle-East Europe)". http://demo.istat.it/str2008/index_e.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Statistics Norway. "Persons with immigrant background by immigration category and country background 1 January 2010". http://www.ssb.no/innvbef_en/tab-2010-04-29-04-en.html. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Refworld. "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Uzbekistan : Meskhetian Turks". http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/refworld/rwmain?page=search&docid=49749c843c&skip=0&query=turks. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ↑ "Japonya Türk Toplumu (Turkish Community of Japan)" (in Turkish). Embassy of Turkey in Japan. http://www.turkey.jp/tr/konsoloslukjaptoplum.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Zouboulis 2003, 55.

- ↑ Migdal 2004, 142.

- ↑ Extra & Gorter 2001, 415.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau: American FactFinder. "2008 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-ds_name=ACS_2008_1YR_G00_&-_lang=en&-redoLog=true&-mt_name=ACS_2008_1YR_G2000_B04003&-format=&-CONTEXT=dt. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ↑ Karpat 2004, 627.

- ↑ TheSophiaEcho. "Turkish Bulgarians fastest-growing group of immigrants in The Netherlands". http://www.sofiaecho.com/2009/07/21/758628_turkish-bulgarians-fastest-growing-group-of-immigrants-in-the-netherlands. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ Hatay 2007, 40.

- ↑ Hüssein 2007, 20.

- ↑ Western Thrace Minority University Graduates Association 2009, 6.

- ↑ MigrantsInGreece. "Data on immigrants in Greece, from Census 2001, Legalization applications 1998, and valid Residence Permits, 2004". http://www.migrantsingreece.org/transpartner/Tables.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ Laczko, Stacher & Klekowski von Koppenfels 2002, 187.

- ↑ The Federation of Canadian Turkish Associations. "Kanada-Türk Toplumu İstatistikleri". http://www.canturkfed.net/tr/kanadaTurk_toplum_tr.html. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ↑ ORSAM 2010, 13.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Kultegin's Memorial Complex, TÜRIK BITIG Khöshöö Tsaidam Monuments

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Bilge Kagan's Memorial Complex, TÜRIK BITIG Khöshöö Tsaidam Monuments

- ↑ Tonyukuk's Memorial Complex, TÜRIK BITIG Bain Tsokto Monument

- ↑ Peoples of Western Asia By Marshall Cavendish Corporation - "An Introduction to the History of the Turkish Peoples, p. 121-122

- ↑ Deny; Jean Deny, Louis Bazin, Hans Robert Roemer, György Hazai , Wolfgang-Ekkehard Scharlipp (2000). History of the Turkish Peoples in the Pre-Islamic Period. Schwarz. p. 108. ISBN 9783879972838. http://books.google.com/?id=86g2AAAAIAAJ&q=Taspar+Khan&dq=Taspar+Khan.

- ↑ S. Frederick Starr, Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland, M.E. Sharpe, 2004, ISBN 9780765613189, p. 37.

- ↑ Ambros/Andrews/Balim/Golden/Gökalp/Karamustafa, Turks, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, online ed., ret. 2009

- ↑ Mallory, J. P., In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth., (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991), pp. 152.

- ↑ Wink 2002: 60-61

- ↑ Hucker 1975: 136

- ↑ Frucht, Richard C., Eastern Europe, (ABC-CLIO, 2005), pp. 744.

- ↑ Scharlipp, Wolfgang (2000). An Introduction to the Old Turkish Runic Inscriptions. Verlag auf dem Ruffel., Engelschoff. ISBN 393384700X.

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard, The emergence of modern Turkey, (Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1968)

- ↑ Mallory, J. P., In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth., (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991), pp. 147.

- ↑ James Bainbridge. Turkey - Google Kitaplar. Books.google.com.tr. http://books.google.com.tr/books?id=Kz5A0r9Mi5UC&pg=PA41&lpg=PA41&dq=the+country+was+referred+to+turchia&source=bl&ots=tDbNkZPREA&sig=jsbcbhqx1NQoNhST45J58TvxIZw&hl=tr&ei=i0hxTPSSMsmnOIvr-bAL&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCAQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=the%20country%20was%20referred%20to%20turchia&f=false. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Halil Inalcık. "Halil Inalcik. "The Question of the Emergence of the Ottoman State"". h-net.org. http://www.h-net.org/~fisher/hst373/readings/inalcik5.html. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P., In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth., (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991), pp. 261.

- ↑ Concise Britannica Online Seljuq Dynasty article

- ↑ The History of the Seljuq Turks: From the Jami Al-Tawarikh (LINK)

- ↑ Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Oxford History of the Crusades New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0192853643.

- ↑ Gürpınar, Doğan (2004) (PDF). THE SELJUKS OF RUM IN TURKISH REPUBLICAN NATIONALIST HISTORIOGRAPH. Sabancı University. http://digital.sabanciuniv.edu/tezler/tezler/ssbf/master/gurpinard/ana.pdf. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Fleet, Kate (1999) (PDF). European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State. Cambridge University Press. http://assets.cambridge.org/97805216/42217/sample/9780521642217wsc00.pdf. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ (Turkish) Sultan Osman I, Turkish Ministry of Culture website.

- ↑ D. Nicolle, Constantinople 1453: The end of Byzantium, 32

- ↑ Yavuz Sultan Selim Government Retrieved on 2007-09-16

- ↑ The Classical Age, 1453-1600 Retrieved on 2007-09-16

- ↑ Merriman.

- ↑ Mango, Andrew (2000). Ataturk. Overlook. ISBN 1-5856-7011-1.

- ↑ Ahmad, The Making of Modern Turkey, 50

- ↑ Kinross, Ataturk, The Rebirth of a Nation, p. 343

- ↑ Gokcumen O and Schurr T. Genler, Göçler ve Anadolu. Atlas Magazine. 2008

- ↑ Hum Genet (2004) 114 : 127–148 Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia, (Cengiz Cinnioglu at all.), pg. 135

- ↑ Late Medieval Balkan and Asia Minor Population.Josiah C. Russell.Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Oct., 1960), pp. 265-274

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Oguz Article

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. Seljuq Article

- ↑ Peter B. Golden. An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, 1992, S. 224-225.

- ↑ (2001) HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans Tissue Antigens 57 (4), 308–317

- ↑ CIA - The World Factbook Turkish 70-75% (2008)

- ↑ Country Studies: Turkey-Turks

- ↑ Turkish Statistical Institute (2008). "2007 Census, population by provinces". Turkish Statistical Institute. http://report.tuik.gov.tr/reports/rwservlet?adnks=&report=turkiye_il_koy_sehir.RDF&p_kod=1&desformat=html&ENVID=adnksEnv. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Turkish Statistical Institute (2008). "2007 Census,population living in cities". Turkish Statistical Institute. http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=3894. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Gogolin, Ingrid (2005) (PDF). Turks in Europe: Why are we afraid?. The Foreign Policy Centre. http://fpc.org.uk/fsblob/597.pdf. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Federation of Turkish Associations UK. "BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FEDERATION OF TURKISH ASSOCIATIONS IN UK" (PDF). http://www.turkishfederationuk.com/en/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=26. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ↑ Embassy of the Republic of Turkey in London

- ↑ BBC Voices Multilingual Nation. "Turkish today by Viv Edwards". http://www.bbc.co.uk/voices/multilingual/turkish.shtml. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ↑ Twigg, Stephen (2002) (PDF). LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY AND NEW MINORITIES IN EUROPE. Language Policy Division. http://www.coe.int/T/DG4/Linguistic/Source/GogolinEN.pdf. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ US Census. "2006 American Community Survey, Total Ancestry Reported". http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=D&-ds_name=D&-_lang=en&-mt_name=ACS_2006_EST_G2000_B04003. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ↑ Turkish Americans

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Kaya, İbrahim (2003). Social Theory and Later Modernities: The Turkish Experience. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-8532-3898-7. http://books.google.com/?id=0Iy7pJBRgjYC&pg=PA58&lpg=PA58&dq=Turkish+culture.

- ↑ Royal Academy of Arts (2005). "Turks - A Journey of a Thousand Years: 600–1600". Royal Academy of Arts. http://www.turks.org.uk/index.php?pid=8. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ↑ Georg, S., Michalove, P.A., Manaster Ramer, A., Sidwell, P.J.: "Telling general linguists about Altaic", Journal of Linguistics 35 (1999): 65-98 Online abstract and link to free pdf

- ↑ Altaic Family Tree

- ↑ Linguistic Lineage for Turkish

- ↑ Katzner

- ↑ Findley

- ↑ Soucek

- ↑ See Lewis (2002) for a thorough treatment of the Turkish language reform.

- ↑ Necipoğlu, Gülru (1995). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 12. Leiden : E.J. Brill. p. 60. ISBN 9789004103146. OCLC 33228759. http://books.google.com/?id=RtbeBrAHhxgC&pg=PA60&lpg=PA60&dq=Ottoman+Architecture. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ↑ Grabar, Oleg (1985). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 3. Leiden : E.J. Brill,. ISBN 9004076115. http://books.google.com/?id=Xu_L_FJRvUIC&pg=PA92&lpg=PA92&dq=Ottoman+Architecture. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ↑ Davis, Ben (2002). Let's Go Turkey. Macmillan. ISBN 9780312305970.

- ↑ Levine, Lynn (2006). Frommer's Turkey. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9780471785569.

- ↑ Stokes, Martin (2000). Sounds of Anatolia. Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0., pp 396-410.

- ↑ "Traditional Music in Turkey". Medieval.org. http://www.medieval.org/music/world/turkish.html. Retrieved May 20, 2004. The Ottoman Empire included substantial territory which had been under Byzantine or Arabic control, and the substratum of traditional music in Turkey was conditioned by that history.

- ↑ "Suleyman the Magnificent". HyperHistory Biographies. http://www.hyperhistory.net/apwh/bios/b1suleyman.htm. Retrieved April 3, 2006. During his rule as sultan, the Ottoman Empire reached its peak in power and prosperity. Suleyman the Magnificent filled his palace with music and poetry and came to write many compositions of his own.

- ↑ "Ottoman Military Music". MilitaryMusic.com. http://www.militarymusic.com/200302.htm#anchor5. Retrieved February 11, 2003.

- ↑ "Introduction to Sufi Music and Ritual in Turkey". Middle East Studies Association of North America. http://www.alevibektasi.org/xsufi_music.htm. Retrieved December 18, 1995. The tradition of regional variations in the character of folk music prevails all around Anatolia and Thrace even today. The troubadour or minstrel (singer-poets) known as aşık contributed anonymously to this genre for ages.

- ↑ "The Ottoman Music". Tanrıkorur, Cinuçen (Abridged and translated by Dr. Savaş Ş. Barkçin). http://www.turkmusikisi.com/osmanli_musikisi/the_ottoman_music.htm. Retrieved June 26, 2000.

- ↑ "A Levantine life: Giuseppe Donizetti at the Ottoman court". Araci, Emre. The Musical Times. http://www.musicaltimes.co.uk/archive/0203/arac.html. Retrieved October 3, 2002. Famous opera composer Gaetano Donizetti's brother, Giuseppe Donizetti, was invited to become Master of Music to Sultan Mahmud II in 1827.

- ↑ Bellman, Jonathan (1993). The Style Hongrois in the Music of Western Europe. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1-55553-169-5. pp.13-14; see also pp.31-2. According to Jonathan Bellman, it was "evolved from a sort of battle music played by Turkish military bands outside the walls of Vienna during the siege of that city in 1683."

- ↑ Lester 1997; Wolf-Gazo 1996

- ↑ Bezirci, 105–108

- ↑ Paskin 2005

- ↑ Earlier poets, such as Ahmed Hâşim, had experimented with a style of poetry called serbest müstezâd ("free müstezâd"), a type of poetry which alternated long and short lines of verse, but this was not a truly "free" style of verse insofar as it still largely adhered to prosodic conventions (Fuat 2002).

- ↑ Quoted in Halman 1997.

- ↑ The Garip movement was considered to be the "First New" (Birinci Yeni).

- ↑ Çarkoǧlu, Ali (2004). Religion and Politics in Turkey. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-4153-4831-5. http://books.google.com/?id=t5G_zw9exMQC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&dq=Religion+in+Turkey.

Bibliography

- Abrahams, Fred (1996). A threat to "stability": human rights violations in Macedonia. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1564321703.

- Aydıngün, Ayşegül; Harding, Çiğdem Balım; Hoover, Matthew; Kuznetsov, Igor; Swerdlow, Steve (2006). Meskhetian Turks: An Introduction to their History, Culture, and Resettelment Experiences. http://www.cal.org/: Center for Applied Linguistics

- Berlin-Institut (2009). Zur Lage der Integration in Deutschland. http://www.berlin-institut.org: Berlin-Institu für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung

- Council of Europe (2006). Documents: working papers, 2005 ordinary session (second part), 25–29 April 2005, Vol. 3: Documents 10407, 10449-10533. Council of Europe. ISBN 9287157545.

- Duvier, Janine (2009). Immigration and Integration in Germany and England. http://www.lse.ac.uk/: London School of Economics

- Ergener, Rashid; Ergener, Resit (2002). About Turkey: Geography, Economy, Politics, Religion, and Culture. Pilgrims Process. ISBN 0971060967.

- Extra, Guus; Gorter, Durk (2001). The other languages of Europe: demographic, sociolinguistic, and educational perspectives. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1853595098.

- Federation of Turkish Associations in the UK (2008). BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FEDERATION OF TURKISH ASSOCIATIONS IN UK. http://www.turkishfederationuk.com/: Federation of Turkish Associations in the UK

- Hatay, Mete (2007). Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking?. http://www.prio.no/: International Peace Research Institute. ISBN 978-82-7288-244-9

- Human Rights Watch (1993). Open Wounds: Human Rights Abuses in Kosovo. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1564321312.

- Hunter, Shireen (2002). Islam, Europe's second religion: the new social, cultural, and political landscape. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275976092.

- Hüssein, Serkan (2007). Yesterday & Today: Turkish Cypriots of Australia. Serkan Hussein. ISBN 0646477838.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2002). Studies on Ottoman social and political history: selected articles and essays. BRILL. ISBN 9004121013.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2004). Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays. BRILL. ISBN 9004133224.

- Kaya, Ayhan; Kentel, Ferhat (2007). Belgian-Turks A Bridge or a Breach between Turkey and the European Union?. http://www.kbs-frb.be/: King Baudouin Foundation. ISBN 978-90-5130-587-6

- Kibaroğlu, Mustafa; Kibaroğlu, Ayșegül; Halman, Talât Sait (2009). Global security watch Turkey: A reference handbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313345600.

- King Baudouin Foundation (2008). Turkish communities and the EU. http://www.kbs-frb.be/: King Baudouin Foundation

- Knowlton, MaryLee (2005). Macedonia. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 0761418547.

- Laczko, Frank; Stacher, Irene; Klekowski von Koppenfels, Amanda (2002). New challenges for Migration Policy in Central and Eastern Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 906704153X.

- Madianou, Mirca (2005). Mediating the nation: news, audiences and the politics of identity. Routledge Cavendish. ISBN 1844720284.

- Migdal, Joel S. (2004). Boundaries and belonging: states and societies in the struggle to shape identities and local practices. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521835666.

- ORSAM (2010). The forgotten Turks : Turkmens of Lebanon. http://www.orsam.org.tr/en: Center for Middle-Eastern Strategic Studies

- Oustinova-Stjepanovic, Galina (2008). Religion and Politics of Sufi Turks in Macedonia A pre-field proposal. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/: University College London

- Park, Bill (2005). Turkey's policy towards northern Iraq: problems and perspectives. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0415382971.

- Phinnemore, David (2006). The EU and Romania: accession and beyond. The Federal Trust for Education & Research. ISBN 1903403782.

- TRNC PRIME MINISTRY STATE PLANNING ORGANIZATION (2006). TRNC GENERAL POPULATION AND HOUSING UNIT CENSUS. http://www.pekem.org/: TRNC PRIME MINISTRY STATE PLANNING ORGANIZATION

- Vachudová, Milada Anna (2005). Europe undivided: democracy, leverage, and integration after communism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199241198.

- Warrander, Gail; Knaus, Verena (2008). Bradt Travel Guide Kosovo. Springer. ISBN 0306477572.

- Western Thrace Minority University Graduates Association (2009). Western Thrace Turkish Minority. http://www.pekem.org/: Culture and Education Foundation of Western Thrace Minority

- Zouboulis, Christos (2003). Adamantiades-Behçet's Disease. Springer. ISBN 0306477572.

Further reading

|

|

External links

General profiles

- By the BBC News

- By the CIA Factbook

- By the Council of Europe

- By the Economist

- By the US Department of State

People

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||